MicroPython vs. The Cloud: Controlling My Smart AC with an ESP32-C3 SuperMini

Ever since our decades-old AC unit kicked the bucket, and our landlord was kind enough to install a shiny, new, smart AC, I’ve been wanting to study how it works, and thought maybe I could build a touchscreen dashboard powered by some microcontroller for controlling it, with a nice 3D printed case or something, seemed like a neat project.

I waited, and waited, days flew by, and now - time’s up!

Why? because WE’RE MOVING IN A WEEK, and I didn’t get to make that cool-ass gadget.

However, I still wanted to do this project in some capacity, maybe with a simple web UI instead of a touchscreen, since the cool part for this project would be reverse engineering the API.

An ESP32 was the obvious choice - all I need is basic Wi-Fi connectivity really, and since time is so tight and I’m feeling hella rusty in the low-level programming department, and I ditched the touchscreen idea,

I decided to try my hand at MicroPython (for the first time!).

Reverse Engineering the API

Before I could build anything, I needed to understand how the Electra (an Israeli AC brand) app communicates with my AC unit.

I needed a way to intercept the traffic, and I figured it’s probably through a REST API.

Setting Up the Interception Environment

I used Genymotion, an Android emulator, to run the Electra app in a controlled environment. The advantage of Genymotion over a physical phone is that it’s much easier to inject system certificates and intercept HTTPS traffic, plus I could try different phones with different Android versions quite rapidly.

For the actual interception, I used HTTP Toolkit.

It’s a fantastic tool that acts as a man-in-the-middle proxy, allowing you to see all the HTTP/HTTPS requests an app makes.

So the basic setup was:

- Install Genymotion and create an Android virtual device

- Install HTTP Toolkit & intercept HTTPS traffic

- Install the Electra app on the emulator

- ???

- Profit.

What I Found

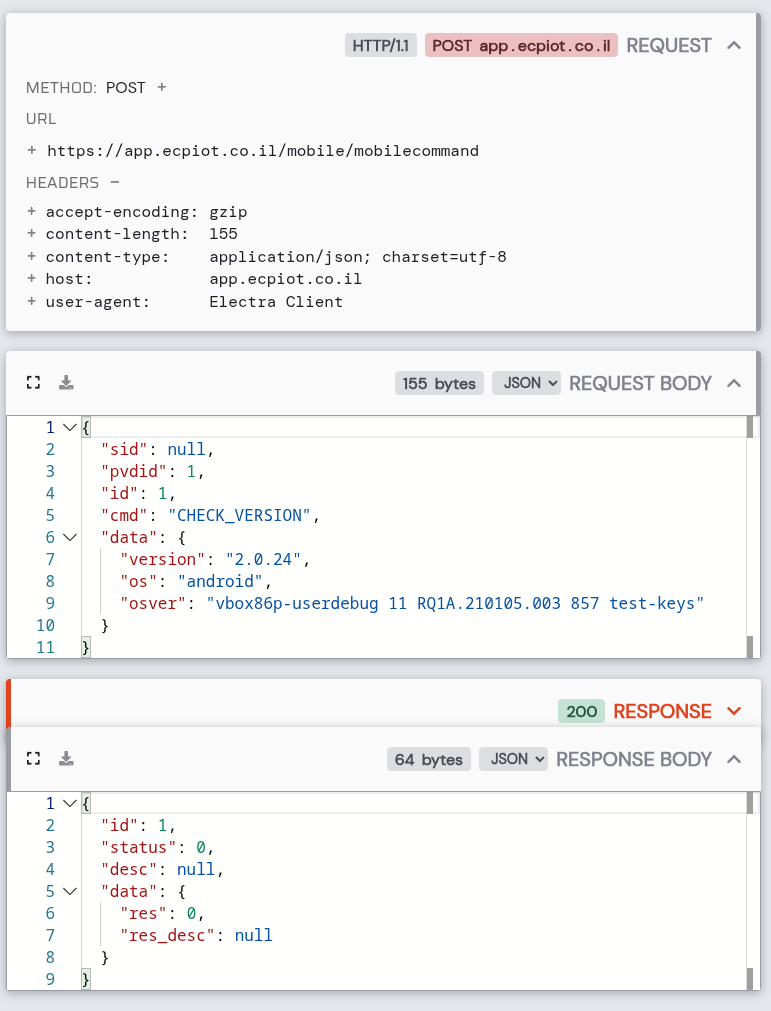

After logging into the app and playing around with the AC controls, I captured several interesting API calls. The Electra API lives at app.ecpiot.co.il and is… janky to say the least.

- All calls use the same API endpoint -

/mobile/mobilecommand - The desired operation is specified in the json body of the request, in the

cmdfield - The

datafield provides data for the operation - The (apparently not so secret…) token and IMEI(!) of the phone are sent within the request’s body(?!)

- All calls use

POSTfor some reason

The first thing the app does is check for updates (to the app, I assume?)

Interestingly, Electra can see I’m running Android on a virtual machine (VirtualBox through Genymotion) with debug capabilities, but don’t seem to care about it.

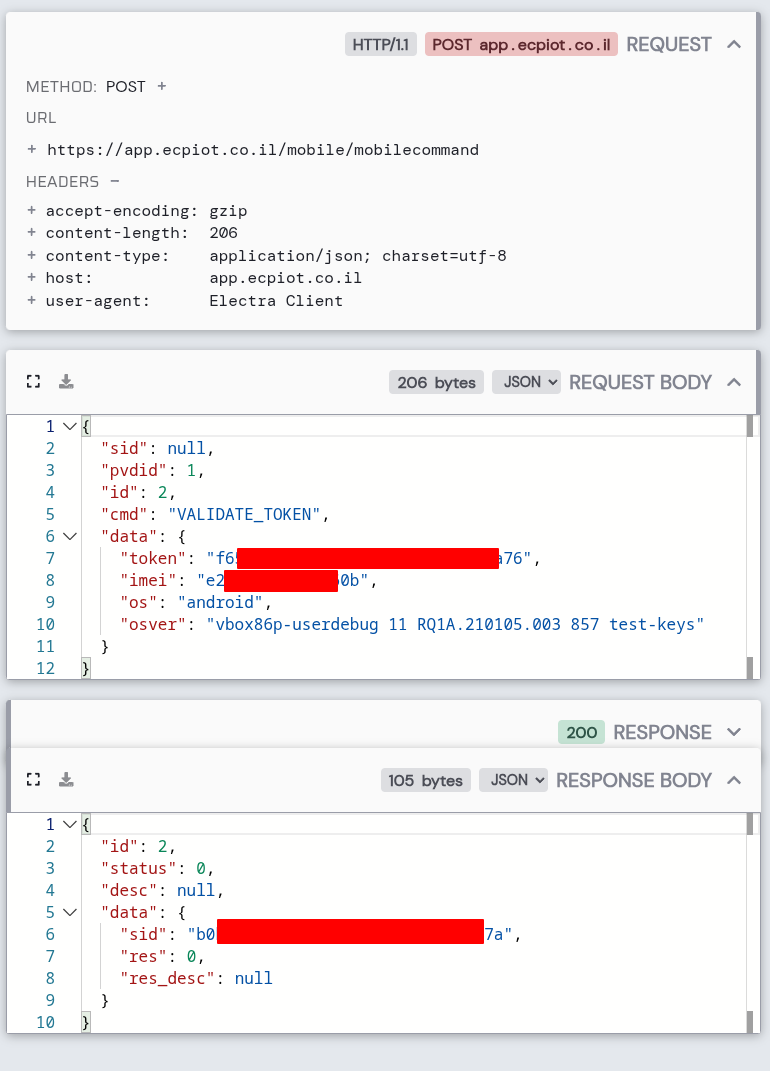

Then, the app validates the token against the remote server, getting a session ID (sid), which will be used in all subsequent calls.

The (apparently not so secret…) token and IMEI(!) of the phone are sent within the request’s body(?!)

This returns a session ID (sid) that’s used for all subsequent requests (Horrible auth but ok).

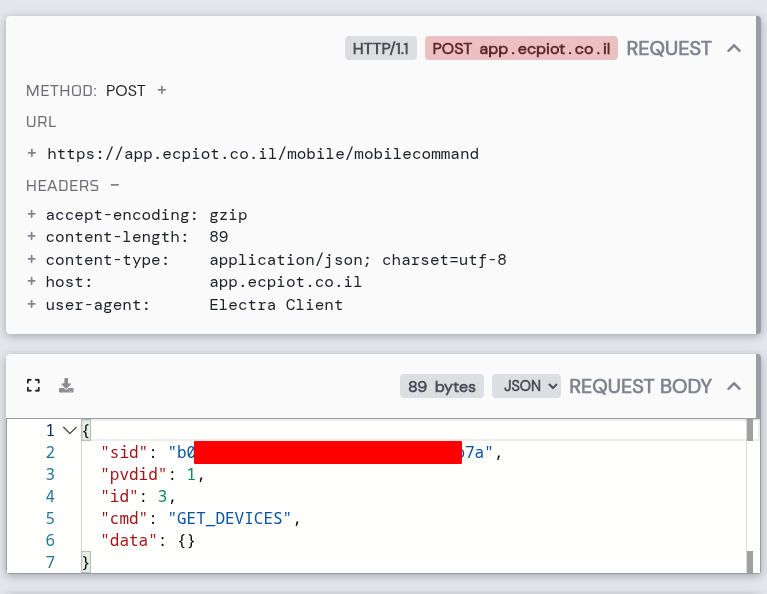

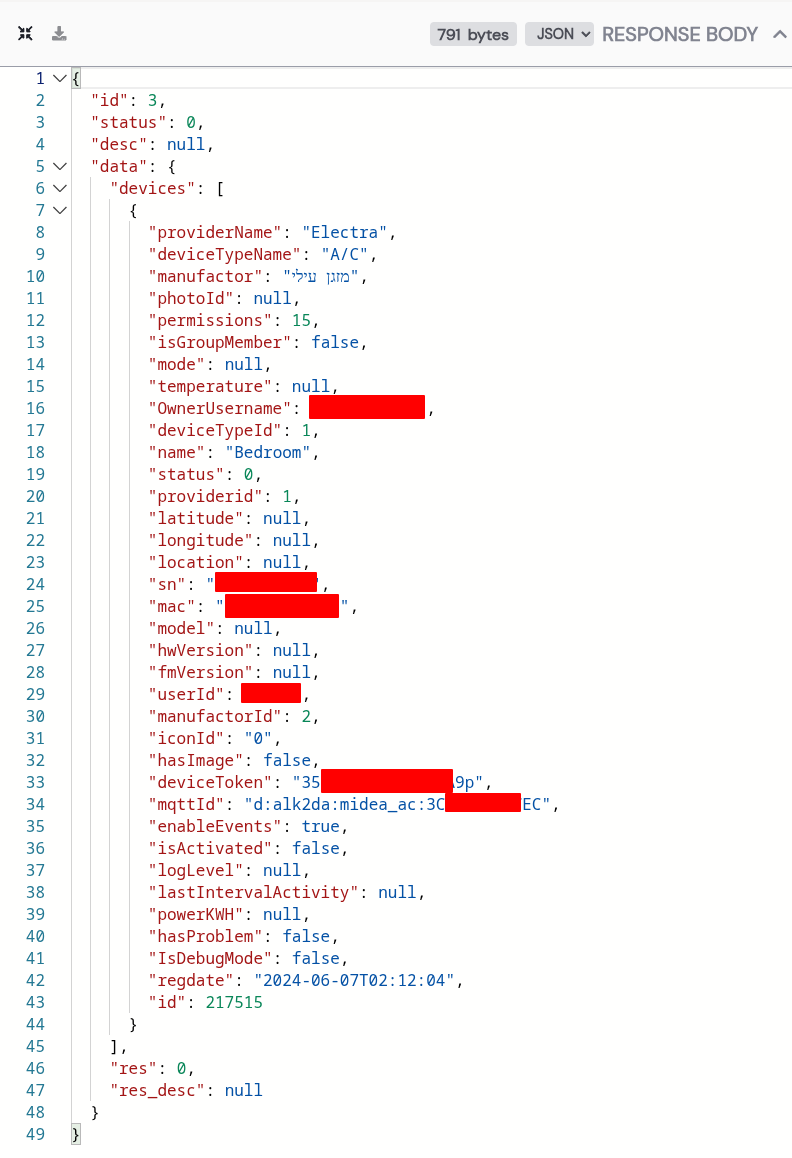

Next, it checks which devices are associated with the account:

Now, if you look at the end of the response, there's the ID of our AC.

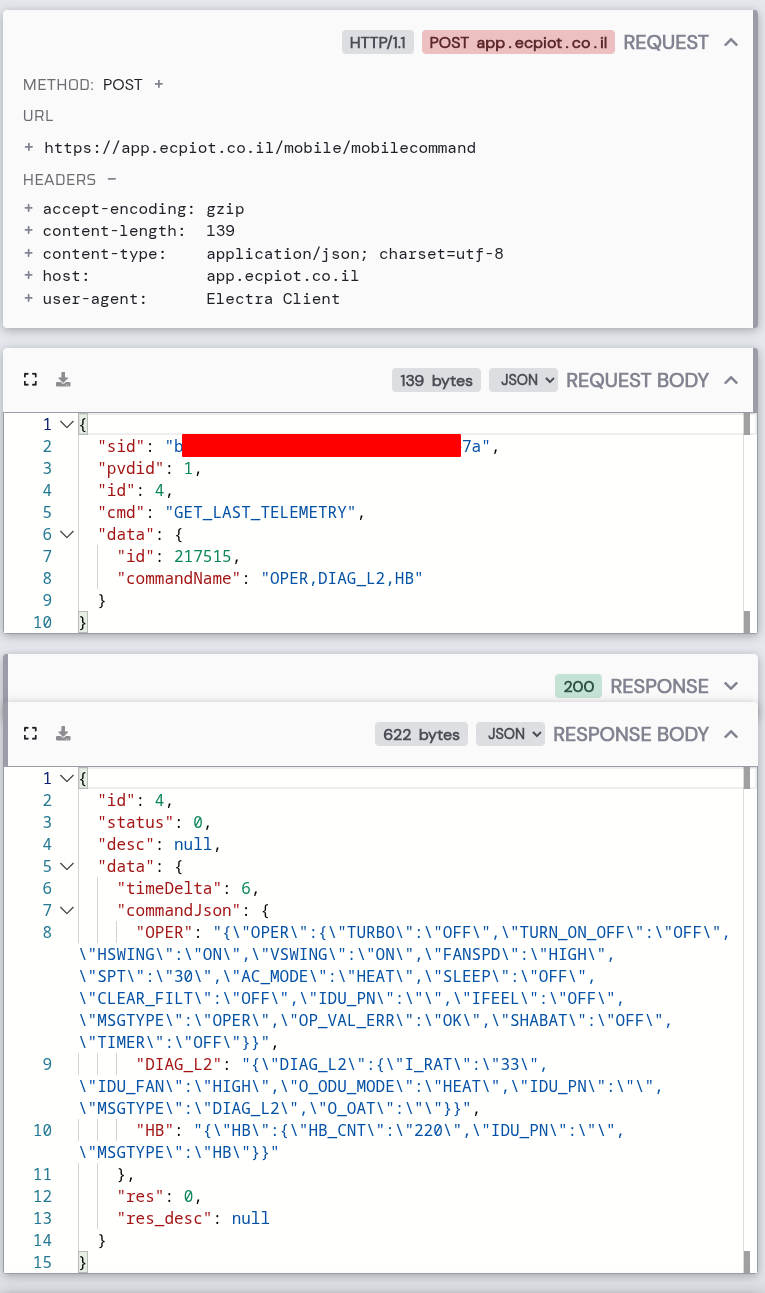

Then, every few seconds, it gets the current AC state (for the ID we just got), with the GET_LAST_TELEMETRY command:

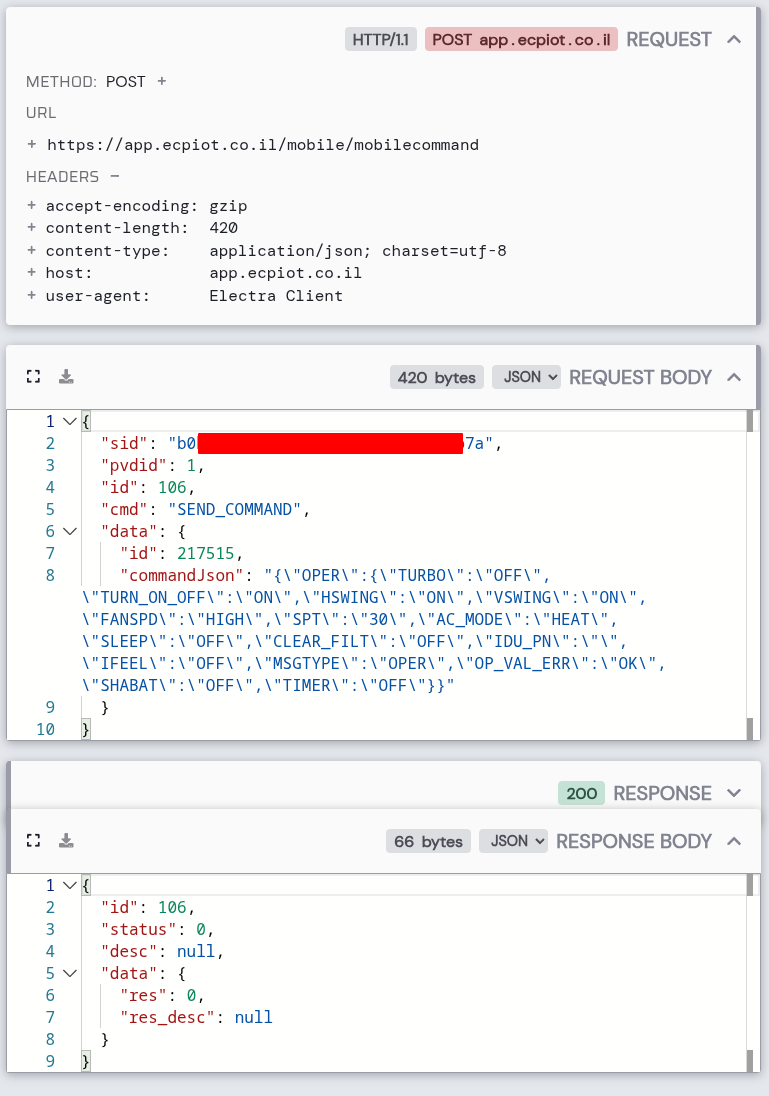

And to control the AC, it sends the entire desired state in a SEND_COMMAND:

The commandJson field is interesting - it’s a JSON string embedded within JSON. A bit awkward, but workable.

Choosing the Hardware

With the API figured out, I needed something to run the web server on. I chose the ESP32-C3 SuperMini for a few reasons:

- Tiny form factor (about the size of my thumb)

- Built-in WiFi

- Runs MicroPython

- Costs about $3

The ESP32-C3 has around 400KB of RAM, which sounds like a lot until you start loading SSL libraries, a web framework, and JSON parsers. Memory management would become a recurring theme in this project.

The First Attempt: Just Make It Work

I started simple. MicroPython has urequests for HTTP calls and ujson for JSON handling. My first script just connected to WiFi, authenticated with the API, and printed the session ID to the serial console so I could see authentication succeeded.

import urequests as requests

import ujson as json

# Connect to WiFi...

def get_ac_sid(url):

body = {

"sid": None,

"pvdid": 1,

"id": 2,

"cmd": "VALIDATE_TOKEN",

"data": {

"token": "my-token",

"imei": "my-device-id",

"os": "android",

"osver": "..."

}

}

headers = {

"Content-Type": "application/json; charset=utf-8",

"Accept-Encoding": "gzip",

"User-Agent": "Electra Client",

"Connection": "close"

}

r = requests.post(f"{url}/mobile/mobilecommand", json=body, headers=headers)

return r.json()

sid = get_ac_sid(ac_url)["data"]["sid"]

print(f"SID: {sid}")This worked! I could see the SID printed in the console. But then I tried to fetch the telemetry and got my first memory-related error.

The GZIP Problem

The Electra app requests gzip-compressed responses from the server, so I did too.

However, decompressing gzip requires a 32KB buffer, and combined with the SSL connection overhead, the ESP32 just couldn’t handle it.

The fix was embarrassingly simple: change the header to Accept-Encoding: identity. This tells the server to send uncompressed data. Slightly more bandwidth, but the ESP32 could actually process it.

Adding a Web Interface

Once I could reliably communicate with the API, I wanted a web interface. I chose Microdot - a Flask-like web framework designed for MicroPython.

It’s not in the official MicroPython package index, so I had to grab it directly from GitHub:

mpremote mip install github:miguelgrinberg/microdot/src/microdot/microdot.pyMy first web server was just a “Hello from ESP32!” page. When that loaded in my browser, I felt unreasonably proud. Then I needed to make a UI, and for that I leveraged Claude Code (I’m not a frontend dev, sue me).

Memory Wars

Getting the web server and API calls to coexist was tricky. The ESP32-C3 has limited RAM, and I was constantly fighting memory pressure left and right.

The solution was aggressive garbage collection. Before every API call:

import gc

gc.collect()I also learned to close response objects immediately after reading them:

r = requests.post(url, json=body)

result = r.json()

r.close() # Free that memory!With these optimizations, I had around 117KB of free memory during normal operation - plenty of headroom.

Making It Responsive

The first version worked, but it was slow. Pressing a button meant:

- Browser sends POST to ESP32

- ESP32 fetches current AC state from API (1-2 seconds)

- ESP32 sends command to API (1-2 seconds)

- ESP32 redirects browser

- Browser fetches new page

- ESP32 fetches state again for display (1-2 seconds)

That’s 5+ seconds of waiting just to change the temperature.

I implemented three optimizations (again, with the help of Claude Code):

1. State Caching - Instead of fetching the AC state before every command, I cache the last known state and use that.

2. Optimistic UI - The JavaScript updates the UI immediately when you press a button, before the server even responds.

3. AJAX Instead of Forms - Using fetch() API calls instead of form submissions means no page reload. (I learned something new!)

The result? The UI is still kind of shit 💀.

mainly because it’s just a little too heavy for this tiny board.

I’d be able to press 1 or 2 buttons before it would completly hang and I’d get connections resetting left and right.

The API though? Chef’s kiss! curling a command to the ESP32 is honestly impressively fast and stable.

The Final Architecture

The project ended up with this file structure:

boot.py - WiFi connection, API authentication

ac.py - Electra API functions

web.py - Microdot web server and routes

templates.py - HTML/CSS/JavaScript template

main.py - Just starts the web server reallyOn power-up:

boot.pyruns first - connects to WiFi, gets the session IDmain.pystarts the Microdot server on port 80- ???

- Profit.

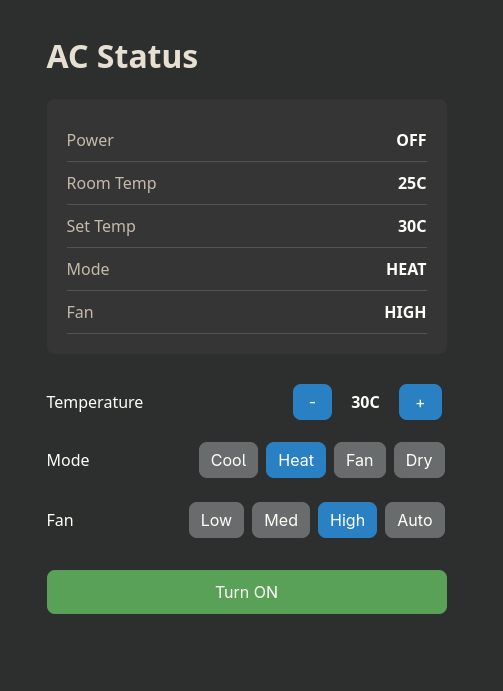

The web interface shows the current state (power, room temperature, set temperature, mode, fan speed) and has buttons to control everything. It auto-refreshes every 10 seconds to stay in sync with the actual AC state.

Lessons Learned

Memory is precious on microcontrollers. Every byte counts. Use gc.collect() liberally, close connections immediately, and think twice about the “work cost” of adding a feature.

Reverse engineering APIs is fun. With the right tools (Genymotion + HTTP Toolkit), it’s surprisingly straightforward to see what apps are doing behind the scenes.

MicroPython is great for rapid prototyping. Being able to iterate quickly without compile cycles made this project much more enjoyable.

The ESP32-C3 SuperMini is impressive. For $3, you get WiFi, plenty of GPIO (which, admittedly, I didn’t use), and enough power to run a web server (albeit a really shitty one). What a time to be alive.

Resources

You can find all the code on GitLab.

- Genymotion Android Emulator

- HTTP Toolkit

- MicroPython

- Microdot Web Framework

- I also came across this article by Aleph Research who actually reverse engineered the hardware, incredible stuff, so it’s an honorable mention for sure.